Global Catholicism: The Church is Changing, But Not How We Might Think

A friend once told me she’d love to be a fly on the wall at Jesuit community dinners. “I’d learn a ton,” she said, implying, I guess, that a tableful of overly educated guys with varied interests could surely produce some profitable conversation. My response was to assure her we spend most dinners arguing over the Patriots chances of winning the Super Bowl or whether Costco’s pumpkin pie is tastier than its pumpkin roll.1

But this dinner was the exception: four American Jesuits of various ideological stripes debating Catholic moral teaching vis-à-vis the HHS contraception mandate. Specifically, we argued whether the old principle of Catholic moral theology, material cooperation, might be applicable to the mandate, and whether, in light of Pope Francis’ priorities, the American episcopacy ought to change its tone – if not its position – regarding its objections to the mandate.

But it was what happened after the dinner that’s since stuck with me. My Jesuit community is impressively international; we’re 57 graduate students studying theology at Boston College (plus a few faculty members) and nearly half of us are non-Americans, citizens of 22 countries (plus Puerto Rico) on six continents. And it happened that this night, having failed to reach an agreement vis-à-vis Obamacare, we decided to take housemate Ignace out to a neighborhood watering hole in celebration of his 39th birthday.

Ignace is from Madagascar and, at that point, had been in the States all of 10 weeks. Entering the pub, he produced his passport for the bouncer, and since it was already out, showed me his U.S. student visa, noting that the State Department had granted him only a three-month stay. Most African members of our community – for example, a Rwandan named Marcel also with us that evening – had two-year visas, and Ignace was keen to explain his theory why he was treated differently. The story he launched into was so long and convoluted – stretching across three decades of Malagasy political history, from independence in 1960 through dictatorships and coup d’états, to a dispute over the legitimacy of its current president who ascended to power after a popular uprising in 2009 – that I cannot hope to reproduce the details for you here.

But what I found intriguing was that the Catholic Church figured prominently into key moments of the story, including its most recent chapter when, in 2009, the archbishop of Madagascar’s capital, one Antananarivo by name, offered a public endorsement of the country’s current president. The U.S. government views this president as illegitimate since he came to power via coup. All this to say: my new friend and Jesuit brother Ignace suspected that visa woes had much to do with his archbishop’s support of a politician not favored by America.

Later in the evening , Ignace explained that Madagascar’s Catholics, who comprise 20 percent of the population, are in a precarious position. In a country in which 90 percent of the population survives on less than $2 a day, Catholics stand on the very lowest rungs of the social ladder. For historical reasons, Protestants have more money and hold more power: “Just look at the churches on Sunday mornings,” Ignace said, “many cars in front of the Protestant churches. No cars at Catholic churches – the Catholics all walk.” Ignace was not surprised that the archbishop, facing an impoverished flock, had endorsed a reform-minded Roman Catholic politician as president, even if said politician was viewed by the West as the mastermind of a coup.

Curiosity piqued, I asked Ignace to list the top issues facing the church in Madagascar and without hesitating, he replied, “Poverty, number one.” No surprise there. Even Ignace’s own family, well-to-do by Malagasy standards (i.e., they’re not starving), suffers from critically limited access to water, sporadic electricity, and health care that’d make Obamacare’s Bronze Plan look like a Cadillac of health coverage. Ignace went on to explain that globalization had been a mixed bag for Madagascar: on the one hand, it brought desperately needed American manufacturing jobs; on the other, the country’s political and economic elite reaped many of its benefits, thus precipitating the 2009 coup.2 Ignace went on to list other concerns: tensions between priests and their parishioners over finances, the odd reality that Jesuit Catholic high schools had trained some of the country’s most corrupt politicians, a lack of educational opportunities, and much, much more.

Later that night, feeling a bit overwhelmed by the evening’s conversation, all I could do was laugh. Laugh, I suppose, at my ignorance. Laugh at the fact that, overly educated American that I am, I could not have told you the name of Madagascar’s capital city, let alone anything about its dicey political history or the manifold and overwhelming problems confronting its Catholic populace prior to my conversation that evening.

Laugh, too, because at the outset of the evening, I’d been discussing the HHS mandate as if it were quite possibly the most pressing agenda item in Francis’ portfolio.

***

After the conversation with Ignace, I resolved to poll every non-Western member of my community

|

regarding the most urgent problems confronting the church in his home country. I polled them all – Japanese, Indonesian, Singaporean, Nigerian, Kenyan, Chilean, Brazilian, Tanzanian, Turkish, Mexican, Syrian, Rwandan, Filipino. Poverty made the top #1 or #2 of all but three lists. Other top vote-getters among the Africans

included: tribal tensions, HIV/AIDS, reconciliation after genocide, the rise of an aggressive form of evangelical Protestantism. Central and South Americans often mentioned evangelicals, drugs, and lack of educational opportunities. Many of the Asians mentioned poverty, too, as well as interreligious issues, i.e., the challenges of co-existing in multi-religious societies in which Catholic Christians were minorities. Clericalism and lay-cleric tensions were mentioned by nearly everyone I talked to.

All this polling took several days, and led to several other late-night conversations with community mates. It wasn’t until a week or so later, in a quiet moment of reflection, that I began to realize this exercise was affecting me in ways I’d not anticipated. Frankly, the whole thing had depressed me, and also left me feeling guilty at my ignorance. From hemen I lived with, I heard anecdote after anecdote of personal and communal hardships, of Catholics navigating problems so much more pressing than those I faced, in parts of the world I’d struggle to locate on a map. What shook me again and again was how removed their concerns were from the ones I spend most of my time debating on Twitter and at the dinner table. There was not a single mention of contraception (except obliquely, in relation to the HIV/AIDS question) – nor women’s ordination, abortion, liturgical disputes, or religious liberty (a few mentions of all-out religious persecution though – of the death-threat variety.)

And turns out, I’m not the only American guilty of solipsism in ecclesiastical matters. In fact, I’m hard pressed to find a commentator who doesn’t mention those “hot button” western cultural issues, and even more hard pressed to find any who seriously contend with Pope Francis qua churchman-from-the-global-south.

Ross Douthat of The New York Times is a good case in point. Douthat is always a stimulating read on religious issues – a center-right Catholic convert whose stuff is rarely short on acerbity or balance. But in two recent commentaries in which he outlines what he views as the core of Francis’ agenda (here and here) you will find no direct mention – not one – of a context beyond America and Western Europe. Douthat sees Francis’s central aim as moving the Church beyond the (western) ideological wars that have plagued it since Vatican II. Douthat argues that by sidelining the divisive cultural issues in favor of themes like poverty and mercy, Francis is attempting to forge a new “Catholic middle.”

I find merit in Douthat’s argument, but it’s telling that he views Francis’ central mission exclusively in terms of conflicts in the western, developed world. What I’ve begun to suspect, especially after these conversations with the international Jesuits of my community, is that maybe Francis is up to something else. Could it be that when he steers clear of contraception and instead focuses on the plight of migrants, his primary intent isn’t bridging ideological divides in the West but addressing the most pressing issues that daily confront the great mass of the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics? Could it be that he prioritizes Catholics dying of poverty in Madagascar over an American battle over healthcare?

Maybe this is what happens when you elect a Pope from the global South: the North’s issues get downgraded. Benedict XVI is a European who staked his papacy on saving western Christianity – the New Evangelization. Perhaps the first Pope from the South, 69% of whose constituents, like him, hail from outside North America and Europe, is intentionally putting the agenda of the global south in the driver’s seat and saying to the rest of us: climb aboard.

***

I think a strong case can be made that this is precisely what’s happening, and moreover, that the shift has been brewing for some time, even as the West has failed to take notice. In 1994, John Paul II announced his intention of holding a synod of Asian bishops. The Roman Curia prepared a lineamenta, a preparatory document outlining the principle agenda items the synod was to address, that they sent off to the Asian bishops conferences. The response from Asia was stunning; even at the time, it should have given the West an intimation of the direction things were starting to head.

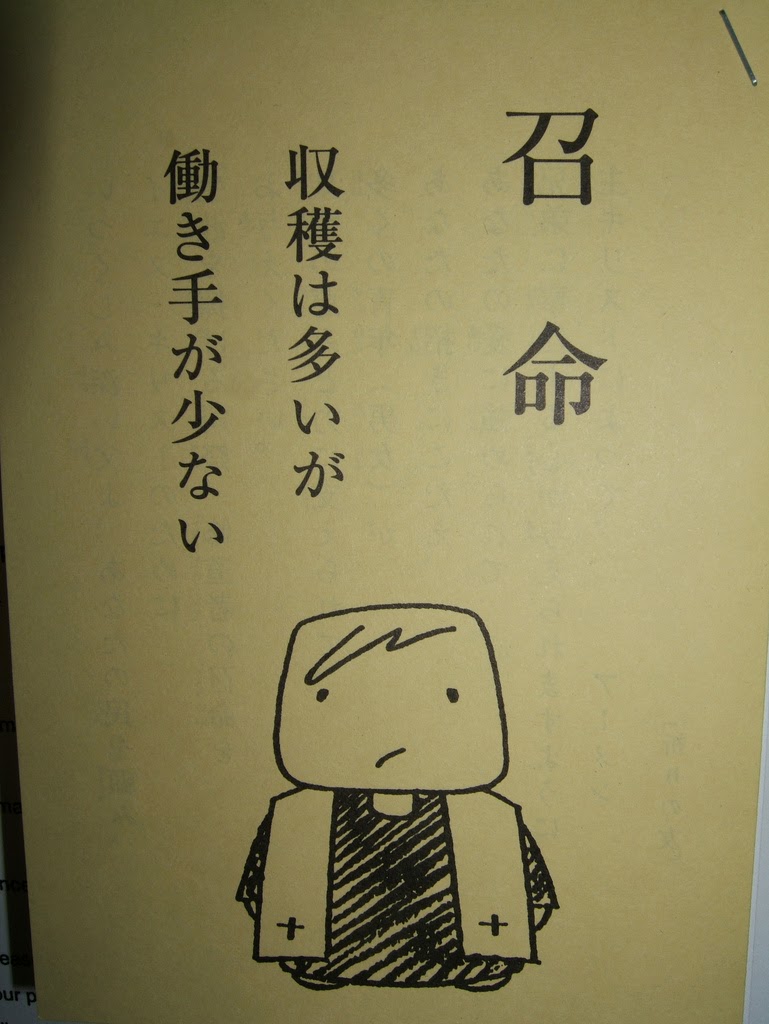

The Japanese Bishops Conference penned a bold rejection of the agenda set by Rome in which it declared, “Since the questions of the lineamenta were composed in the context of Western Christianity, they are not suitable. From the way the questions are proposed, one feels that the holding of the synod is like an occasion for the central office to evaluate the performance of the branch offices.”3 The bishops went on to critique the language of evangelization employed in the lineamenta, rejecting it as unworkable in a cultural context in which Christians were “in a minority position with and for others.” They went on:

“If we stress too much that ‘Jesus Christ is the one and only savior,’ we can have no dialogue, common living or solidarity with other religions. The church, learning from the ‘kenosis’ of Jesus Christ, should be humble and open its heart to other religions to deepen its understanding of the mystery of Christ.”

Re-reading the bishops’ response in the wake of Francis’ election, I’m struck that many of the Pope’s key agenda items appear lifted directly from the pages of their text, in particular Francis’ apparent desire to shift the tone of the New Evangelization from doctrine to witness. The section quoted above aligns quite well with the pope’s observation in that immediately famous America interview. There he said:

“The church’s pastoral ministry cannot be obsessed with the transmission of a disjointed multitude of doctrines to be imposed insistently…. We have to find a new balance; otherwise even the moral edifice of the church is likely to fall like a house of cards, losing the freshness and fragrance of the Gospel.”

The Pope’s focus on dialogue and his remark to an Italian newspaperman that “proselytism is solemn nonsense… we need to get to know each other, listen to each other and improve our knowledge of the world around us,” fits precisely the reality about which the Japanese bishops speak. And that’s far from all that he’s done.

Take Francis’ elevation to the cardinalate of Archbishop Orlando Quevedo of Cotabato in the Philippines, for example. While inside Asia Quevedo is well known as an intellectual heavyweight,4 this was an appointment that seemed to many to come out of left field. That Quevedo has been chosen lends credence to the idea that Francis’ ecclesiological vision coincides with the vision coming out of Asia – a church which is less centralized, more local, and which responds to the issues that most affect local flocks, poverty being issue numero uno. Quevedo has written extensively on these issues, developing what the Asian Federation calls a “triple dialogue,” in which the local church is to be in touch with (1) local cultures, (2) local religions, and the (3) local poor who comprise the majority of the Asian churches.

An even more striking similitude is the Japanese bishops’ contention that “compassion with the suffering” and solidarity with the poor must be “the central evangelization theme.” As the Japanese bishops make clear in the letter mentioned above, this concern was not theirs alone but one that emerged again and again out of meetings of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conference. Even an Asian churchmen less theologically adventuresome than many of the Japanese, the Indonesian Cardinal Julius Darmaatmadja, would assert in a 1999 post-synod reflection that the Asian church had yet to take on “the face of Asia.”

In a cultural context in which Christians are a minor

ity, and in which poverty is widespread and systemic, the

reality of the poor must be the departure point for evangelization if the Christian message is to have any credibility whatsoever.5 The message of the Asian bishops was clear, and Francis seems to be listening.

This past October, Adolfo Nicolás, the Superior General of the Jesuits, paid a visit to my community in Boston – another occasion when our dinner conversation strayed away from Costco desserts. And Nicolás spent considerable time explaining his own views about what Pope Francis is up to.

Like Francis, Nicolás has also spent the majority of his ministerial career outside the West; he studied and taught theology in Japan before becoming provincial of the Japanese province, and then head of all the Jesuits in Eastern Asia and Oceana. In his talk to my community, Nicolás related an anecdote from his tenure as provincial. Fr. Nicolás had befriended a Japanese bishop from Tokyo named Kazuhiro Mori. And once, when the two were conversing, Bishop Mori observed to him (I paraphrase): you westerners are so obsessed with truth – the truth of this or that doctrine, the orthodox belief – but that is not what Asians find compelling. In our intellectual traditions, our focus is on the way, e.g., the Taoist way, the way of the Buddha. So please, the bishop admonished Nicolás, never forget that Jesus says he is not only the truth, but also the way and the life! (cf. Jn 14:6).

Most of the American Jesuits in the room that night had spent time living outside the States – ministry experiences in the developing world are a built-in component of our Jesuit training – yet, as our big boss dropped those words, I saw surprise on many of our American faces. This was a way of considering Jesus that could sound nearly heretical to western ears. But the message from our fellow Christians in Asia conveyed to us by Fr. Nicolás was that this notion of Jesus, a Jesus who is not primarily a purveyor of doctrinal truths but a model for living a fecund and fulfilling life, was right there in the Bible.

Nicolás went on to suggest that while a concern for “truth” has long dominated a western-lead Church, that focus must now be tempered by values Asia and the global South bring to the table. In Nicolás’ understanding, Asian Christians had much to teach the global church about the necessity of the “way,” while Africa and Latin America could teach us of the “life.” In light of these considerations, Nicolás proposed to us that we might frame the global Christian journey as: “On the way. In truth and life.”

Peter Phan is a Vietnamese priest and theologian who’s spent the past several years trying to get western Catholics to wake up to the reality of the coming global church. At a lecture of his that I attended in Boston in 2010, Phan acknowledged that the Japanese bishops lost the battle over the ’98 synod and Rome got the agenda it wanted. But, one day soon, he predicted, Rome would be forced to hear non-European voices. It was a simple matter of demographics, he said. It is true that, by 2050, four out of every five Catholics will live in the southern hemisphere and, according to Phan, “a white Christian [will be] an oxymoron.”

This is a shift I find staggering to contemplate. Whatever the church ends up looking like in 2050, the days of western centralization are numbered. So from here on out, I’ve resolved to spend a lot more time paying attention to the issues concerning my non-western housemates, trying to heed Phan’s words to a recent audience in California, “Wake up! This is the reality you cannot avoid.”

No we cannot. It seems to me that Phan and the Japanese bishops weren’t wrong, they just arrived early. And perhaps now their wait is over; the seismic shift is underway. Perhaps Pope Francis is only the beginning. For we western Christians such shifts will surely cause us consternation, so accustomed, as we are, to our issues driving the global discourse in matters ecclesiastical and otherwise. But perhaps that’s not a bad thing for us; for as someone once said, “the first shall be last and the last shall be first.”

The cover picture can be found at Flickr here.

– — // — –

1. Actual argument at an actual dinner last month. Punches were nearly thrown. ↩

2. In 2009, a charismatic young mayor of Antananarivo named Andry Rajoelina led a series of public demonstrations that led ultimately to the ouster of Madagascar’s president Marc Ravalomanana and to his installation as “President of the High Transitional Authority of Madagascar.” Rajoelina had been a vocal critic of many policies of Ravalomanana’s administration, in particular, its decision to lease half of Madagascar’s arable lands to the Korean multinational Daewoo and the purchase of a second presidential jet with a $60 million price tag. Rajoelina’s coup capitalized on widespread public sentiments that national development was benefiting only a small elite. ↩

3. The full text of the bishops’ response is available in English translation on the website of the Catholic Bishop’s Conference of Japan: http://www.cbcj.catholic.jp/eng/edoc/linea.htm – I wonder if the fact it’s still prominently available on the website is an indication the bishops haven’t had a change of heart in the two intervening decades since its publication. ↩

4. A recent National Catholic Reporter editorial called him “the chief living intellectual architect of the pastoral ideas coming out of the 42-year-old Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences.” ↩

5. Just last week, the Japanese bishops were at it again, issuing a statement in advance of this October’s General Synod on the Family. The bishops are blunt in charging that “there is a big gap between the Vatican and reality” on matters of family life and sexual morality. And they again critique the Curia for a Western-centric focus that neglects the reality of non-European contexts, citing as one example the church’s attitude toward interreligious marriage. Responding to a curia-issued preparatory survey in advance of the synod, they argue, “The questions and topics of this survey have been developed with the mindset of Christian countries in which the entire family is Christian. For example, religiously mixed marriages seem to be considered a problem. However, in Japan, the overwhelming majority of marriages involve mixed religions.” The entire statement can be read as a PDF here. ↩